By Karl Davis

Originally published January, 2019

Nestled in the foothills of the Blue Mountains in northeast Oregon, Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts has been serving Native American artists for the past 26 years, primarily through its artist-in-residency and print publishing program. Crow’s Shadow is located on the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, a checkerboard of ownership and competing interests since the incursion of white people into the area in the nineteenth century. In 1855, the Cayuse, Walla Walla, and Umatilla tribes negotiated a treaty that would cede over 6.5 million acres to the United States government in exchange for 250,000 acres of homeland for the three tribes. Later in the century, legislation reduced that area to just over 178,000 acres, with large tracts within the reservation handed over to white settlers for farming and ranching.

While the results of these laws are not always visible to an outsider, for some of the artists in residence at Crow’s Shadow, the impact of U.S. policies on the reservation is a very present reminder of their own history and connection to the land. The landscape often becomes a preoccupation during their residencies, even when it is not a primary concern in their own studio practice, evoking the lasting connections Native artists have with the land and languages that bind them to their respective cultures. For James Lavadour (Walla Walla), a direct relationship emerges in his work to the power and energy of the land itself; for Wendy Red Star (Crow/Apsáalooke), it is a study of her ancestors and their histories; and for Demian DinéYazhi’ (Diné), it is a respectful tribute to his immediate relatives.

Lavadour founded Crow’s Shadow in 1992 in response to the lack of professional opportunities for the creative people of his home reservation. In the ensuing years, the Institute’s mission expanded to include fine-art print publishing for Native artists from across North America, selected for two-week residencies by a committee of Crow’s Shadow staff, board members, and external artistic advisors. Through a grant from The Ford Family Foundation of Roseburg, Oregon, Red Star and DinéYazhi’, who both live and work in Portland, received Golden Spot Awards to attend their residencies; Lavadour still lives on the reservation (his studio is a five-minute drive from Crow’s Shadow) and usually produces at least one edition of lithographs on a biannual basis.

Informing all Lavadour’s work is an early experience of nature which he often describes as a kind of epiphany. One day on a hike near his childhood home, he was clambering across a small creek and grabbed a fallen tree branch to steady him. As he was holding the branch he realized that the other end of it was lodged upstream, and the water flowing over the branch was moving it in his hands. The sudden sensation that energy was flowing through the ground and the water and through him back into the land was overwhelming. From that point on, his art took on a new direction. His prints and paintings convey his embodied experience of the earth through both their subject matter and process.

The oil paintings comprise multiple layers applied over the course of many months or even years; a layer may then be scraped or scratched, revealing the layer below. In this way, the paintings become geologic, evoking a landscape formed over millennia of upheaval, stratification, and erosion. Lavadour often organizes his paintings into grids, where each panel remains a unique composition while the overall arrangement is unified through a shared palette and evocative mark-making. The repeated elements on different panels become markers for the passing of geologic eras, time-lapse images suggesting a mountain’s formation and subsequent erosion through millions of years.

Lavadour’s latest print at Crow’s Shadow, a diptych of two lithographs titled This Good Land (2017, fig. 1) and meant to be stacked one above the other, continues his preoccupation with the regional environment experienced through time. Here the artist, without the ability to pull back layers of paint, must consider his composition from the bottom layer up—typically a printer will work from the lightest layer of ink to the darkest—and relies largely on color and its associations to convey his content. In This Good Land, Lavadour creates luminescent backgrounds while superimposing dark reds, greens, and black. The different shades of blue in the two respective lithos recall different times of day, perhaps the darkening cobalt of dusk or the piercing azure of a mid-day summer sky. The verdant green of the upper print transitions to gold, echoing the wheat fields that stretch across the rolling hills of the Columbia Plateau. The red and yellow of the lower print recall the summer wildfires that return each year in seemingly greater strength, leaving behind a charred black landscape.

Red Star’s Crow’s Shadow prints are direct investigations and reflections of modern life on an Indian Reservation, in keeping with her overall practice which incorporates photography, installation, conceptual objects, and traditional Indigenous arts. Her work is at once deeply personal and pointedly political. A single installation might include hand-annotated photos of her ancestors and relatives, tongue-in-cheek evocations of dime-store romance novels with Red Star herself as the central figure, an elaborate regalia dress made completely out of tire inner-tubes, or a hand-drawn map covering an entire wall with the names of all members of the Crow Nation photographed by Edward Curtis. Her prints examine her ancestral history as well as her experience as a Native artist navigating a contemporary society dominated by cultural appropriation and assimilation.

In The (HUD) (2010, fig. 2), she presents a tower of houses piled on top of each other, climbing into a sky of chartreuse and silver. She photographed the houses around the Crow reservation; all were built by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development at the direction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, starting in the 1970s and continuing today. Such houses are also built on the Umatilla Indian Reservation and no doubt on many reservations across North America. Each structure is a single story, usually made of cement block or other low-quality material, designed without consideration for its intended location. To personalize and distinguish their homes, Crow residents have painted them in bright purples, yellows, greens, and reds. The uniformity of each house is thus belied by its unique palette. In Red Star’s print, the stack of homes reaches into the heavens, at once a celebration of color and a repudiation of the living conditions to which the Apsáalooke are subjected.

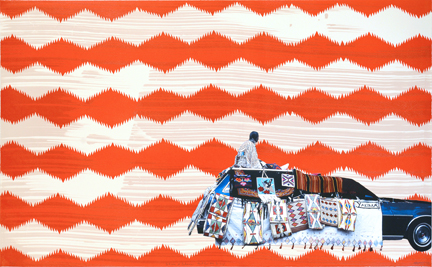

Two later prints, Yakima or Yakama, Not for Me to Say and iilaalée = car (goes by itself) + ii = by means of which + dáanniili = we parade (both 2015, figs. 3 and 4, respectively), display images of parading cars against re-appropriated blanket patterns made popular by the Pendleton Woolen Mills since the early twentieth century. The background of the former print is a stunning red “eye-dazzler” arrangement of saw-toothed zigzags, hand drawn by Red Star to mimic a woven fabric. The main image derives from a photograph taken by Red Star’s uncle in the 1970s at Crow Fair, an annual gathering of the three distinct bands of the Crow/Apsáalooke people. Adorned with parfleche bags, blankets, and other objects of personal significance, the festive station wagon drives off the lower right of the composition. Atop the car is a solitary female figure. This vehicle and its rider would have been participating in a traditional procession—once of horses, now of automobiles—celebrating the wealth, property, and personal success of the rider and, by extension, her family. Red Star’s title refers to the tribal name inscribed on one of the blankets, Yakima. Just as the Crow people have returned to the autonym “Apsáalooke,” so are other tribal entities throughout North America reclaiming their ancestral and traditional names instead of the monikers imposed by white settler colonialists. The Yakima/Yakama people are from what is now southern central Washington State. Red Star refuses to take a position on the spelling of their name, declaring plainly, “It’s not for me to say.” As an outsider to the Yakima, she honors their tribal sovereignty and their prerogative to name themselves.

The lithograph iilaalée = car (goes by itself)… is another, slightly more contemporary representation of Crow Fair parading vehicles. In the title, Red Star translates the Apsáalooke term for this kind of procession. A whole row of pickup trucks spans the middle of this print, each vehicle laden with blankets, bear skins, and coup sticks (traditional staffs recording warriors’ feats). The trucks’ riders are all female, emphasizing the matrilineal hierarchy of Crow/Apsáalooke society. Once again, a hand-drawn re-interpretation of a Pendleton blanket pattern forms the background, in this case a colorful array of stars, stripes, and diamonds, which renders the image visually overwhelming despite its simple composition. As in Yakima or Yakama, the Pendleton Woolen Mill blanket pattern in this litho symbolizes Native culture appropriated by whites and marketed for mass consumption. At the same time, the artist desires to exhibit or explain Crow culture through a direct presentation of tradition. The Native women themselves, proudly riding on their cars or trucks, hold space on the trade blanket, prominent as both creators and consumers of the cultural product.

Demian DinéYazhi’’s work is similarly personal and political. His blog, Heterogeneoushomosexual, contemplates “Radical Indigenous Queer Feminist Art” and how a marginalized body navigates and resists assimilation. His practice includes curation, zines, public interactions, as well as writing and poetry. As the founder of the arts initiative Radical Indigenous Survivance & Empowerment (R.I.S.E.), DinéYazhi’ focuses on the continuance of Indigenous arts and culture. While in residence at Crow’s Shadow, he produced two prints, both inspired by his Navajo ancestors, language, and memories of the landscape of his home reservation just outside of Gallup, New Mexico. Naasht’ézhí Tábąąhá Girls (2018, fig. 5) frames a tender photograph of his mother and grandmother with intricate geometric abstractions of traditional Navajo weaving patterns. The title of the work refers to his maternal grandmother’s clan within the Navajo Nation, and the text at the center of the lithograph is a dedication of sorts, roughly translated as “my heart remembers my grandmother.” The smaller background pattern invokes his paternal grandmother’s weaving style, while the larger lozenge motifs containing the photographic image are prevalent in his maternal grandmother’s clan. The colors are allusions to Navajo weaving, the arid landscape of the reservation in northwest New Mexico, as well as the dry-land wheat growing right outside Crow’s Shadow front door.

No Place Like Hózhó (2018, fig. 6) is a vibrant, tongue-in-cheek play on words which also pays homage to the artist’s ancestral homeland. The phrase “There’s no place” arcs across both the top and bottom of the print, in alternating red and yellow letters, with “Hózhó” emblazoned in blue in the middle of the composition. A printed photograph of DinéYazhi’’s maternal grandmother’s hogan is repeated in three concentric, six-sided rings, and appears again in the center, discernible through the blue text. The circular arrangement of the photos echoes the traditional footprint of the hogan itself, while the word “Hózhó” loosely translates as a state of peace, wellness, or balance. The hogan is a dwelling as well as a place of healing, ritual, and personal renewal. DinéYazhi’’s print is reminiscent of a tourist’s postcard, with the name of a destination in large bold letters and illustrated with a collage of sightseeing highlights; at the same time, it invokes Dorothy’s incantation in The Wizard of Oz as she pines for Kansas, repeating, “there’s no place like home.” It is a statement of nostalgia and loss, an impossible yearning for that which is no longer and can never be retrieved.

The grainy snapshot of the hogan is like so many photos of a childhood home, this one complete with a barbeque grill and the family dog standing vigil in the motif’s central iteration, but here it is rendered especially poignant: home is sacred, land is power, and language holds precious memories intact. Such sentiments are undoubtedly shared by Red Star and Lavadour and expressed in their own distinctive ways in works created at Crow’s Shadow. Unique to each artist’s individual history and relationship to the reservation, these prints also participate in the larger, empathic project of art—ideally, extending a universally intelligible content to appreciative audiences everywhere.

___

A native Oregonian with strong ties to the local and national arts communities, Karl Davis holds an MA from the University of Alberta and BA from Portland State University, both in art history. He has led a number of arts organizations throughout his career, including as Coordinator of the Littman/White Galleries at PSU, Director of Froelick Gallery in Portland, and President of the Art and Design Graduate Student Association at the University of Alberta. Since 2014, he has been Executive Director of the Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts in Pendleton, Oregon. He has curated exhibitions of Crow’s Shadow prints for numerous venues, including PSU, George Fox University, and the Newport Visual Arts Center. In 2017, in partnership with the Hallie Ford Museum of Art at Willamette University in Salem, Oregon, he organized the traveling exhibition “Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts at 25.”

This essay was edited by Sue Taylor, and is among a series of essays commissioned for the Visual Arts Ecology Project by The Ford Family Foundation with editors Stephanie Snyder, John and Anne Hauberg Curator and Director, The Douglas F. Cooley Memorial Art Gallery; and Sue Taylor, former Associate Dean, College of the Arts and Professor of Art History, Portland State University. The commissioning institutions share a goal to strengthen the visual arts ecology in Oregon, and a key interest of increasing the volume of critical writing on art in our region.