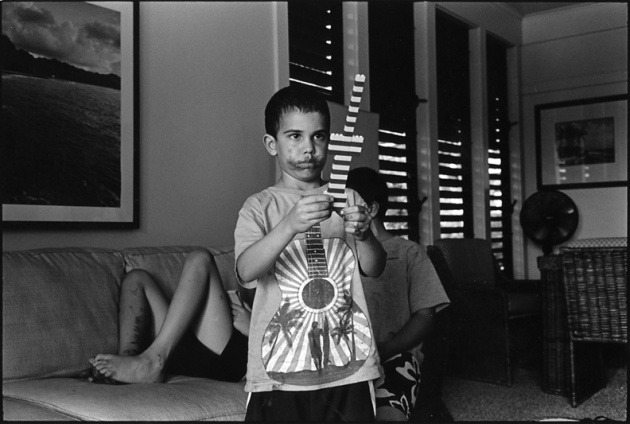

Andrews, Blake. 2013. Emmett. Gelatin silver print.

“Because the past is just a goodbye: Blake Andrews at Blue Sky gallery”

by Patrick Collier

Originally published by Oregon ArtsWatch June 16, 2016

I’ve known about Blake Andrews for many years. He is a force to be reckoned with in the world of photography, particularly because of his minimally titled blog, B. Steeped in the history of and a dialog about photography, the blog is informative, but its real bite comes when Andrews applies his creative, incisive wit—sometimes so dry that how one interprets him says more about the person reading than what he writes—that makes it a must-read. Those who make the mistake of taking him at face value are said to start bleeding a good 24 hours later from the place his scalpel almost imperceptibly pierced their skin.

But we’re here to talk about his exhibit of photographs, specifically his exhibit, Pictures of a gone world at Blue Sky Gallery. All framed by sprocket holes (not visible in the reproductions here), the 28, black and white, analog photographs carefully attend to a specific aesthetic and technical history of his craft. The subject matter is mostly his wife and kids, which some might consider a bit of a throwback. But the images illustrate the title for the exhibit, “Pictures of a gone world,” which, the exhibit’s PR informs us, is also the title of Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s first book of poems.

“Gone?” If I were of a literal bent, I’d see no pending doom in these photographs. (Well, maybe in one photo, but we’ll get to that in a bit.) Quite the contrary: I see joy, even in the most chaotic of moments portrayed in these images, and a lot of fun being had.

Oh! “Gone!” Like in “Gone, Daddy, gone,” as in “far out,” taking things to a new level, or being unconstrained. It is a vernacular older than Andrews; another time lost; still, albeit anachronistic, applicable for this exhibit.

The PR goes on to explain that this exhibit is inspired by a specific Ferlinghetti poem, “The World is a Beautiful Place,” which starts out: “The world is a beautiful place/to be born into/if you don’t mind happiness/not always being/so very much fun.” Continuing the theme, the poem finishes: “Yes the world is the best place of all/for a lot of such things as/making the fun scene/and making the love scene/and making the sad scene/and singing low songs and having inspirations/and walking around/looking at everything/and smelling flowers/and goosing statues/and even thinking/and kissing people and/making babies and wearing pants/and waving hats and/dancing/and going swimming in rivers/on picnics/in the middle of the summer/and just generally/’living it up’/Yes/but then right in the middle of it/comes the smiling/mortician”

I have gone to the bother of transcribing most of this poem for a reason, and it is not because these photographs are not capable of standing on their own. The majority were taken between 2006 and 2010, yet span a slightly longer period of time. As such, they function as a chronicle of his family as they age, and as one might suspect, there is a broad range of emotions portrayed.

Andrews is known as a street photographer, a practice that is said to depend heavily on the “decisive moment,” that critical and optimal split second in which the photo comes together in both form and content within the frame. These street skills become paramount when capturing the half-feral, gleeful chaos that can be found in a child’s exuberance. Even so, to be both parent and photographer must pose some interesting problems: To be both in the moment and outside of it; enjoying/enduring the time in a dual capacity; and then capturing it as best he can. Stopping to appreciate that which has just passed is an indulgence he may not be able to afford, that is if he is to follow the photographer’s dictate: Take it all in, watch, watch, watch to see and be ready before the moment becomes a missed opportunity. (And, I would add, capturing the decisive moment is only an attempt, the actual accomplishment something else, closer, perhaps, to the happy accident in one of ~36 frames.) Only at a later time might he make something of the experience.

Taken as such, the option of staging a photo doesn’t seem like a bad decision. And there is one photo in this group that does have that flavor, a photo that, somewhat understandably, was not available for reproduction here. It shows one of Andrew’s sons at a fairly young age, naked and holding a large pair of garden shears—the limb-lopper variety—in front of himself.

Despite this psychoanalytic show-stopper, I can hear someone ask incredulously, “Pictures of his children are worthy of an exhibition?” and perhaps continue with a litany of photo history references that amount to an argument of “been done a thousand times.” Sure, if the work simulated the times I’ve been trapped on someone’s couch with their photo album in front of me. Instead, Andrew’s combination of the candid moment and his composition skills set a stage from which to dismantle the contempt of even the most hardened, wow-me-now gallery-goers—and perhaps not just the ones who have watched their own children grow.

Still, is the temptation to ask such a question telling of another gone world? There is a certain cynicism as well as disregard that lurks in the contemporary art arena; both attend to our need to expect the unusual. In the face of such a reaction, Andrews might smirk. The yearning for the quirky or unique creates a disconnect, both passive and active (seen that, done that), and manifests as a loss. In spite of all of the obvious fun his kids are having, these images could very well flip around and act as a stand-in for anyone’s loss of innocence or sense of wonder.

On the surface, cynicism is antithetical to sentimentality. A closer look finds something not always easy to perceive, let alone embrace and utilize: cynicism and sentimentality are two sides of the same coin. What if, then, we were to accept this kinship? What if cynicism was just as hackneyed as sentimentality, and just as much from the heart? After all, in the quest for artistic contemporaneity, should we distance ourselves from a substantial part of what has nurtured us?

We learn to anticipate loss. The loss all parents experience as their children’s autonomy burgeons is just one aspect of this life-long lesson. Blake Andrews’ images celebrate playfulness—including his own with a camera—all the while making us look more closely at what we have lost in our sophistication as adults. After all, it is the adult, not the child, who worries about that garden tool.

Courtesy of Oregon ArtsWatch.

Artist Credit: Blake Andrews, Patrick Collier.