A “Working History” at Reed

Amy Bernstein

Originally published by PORT February 05, 2008

The group show at Reed this month is in honor of change and the ability to alter popular notions of thought. Entitled Working History: African American Objects, this exhibit explores the contemporary African American experience through languages both appropriated and created. An amalgam of artists compiled and arranged by Cooley Gallery curator, Stephanie Snyder, this show is a brilliant, reified miasma of African American identity politics that bleeds over its own edges. An empathetic, rich web, Snyder executes this discussion with kaleidoscopic resonance

Walking into the gallery you are met by the faceless deity of artist Nick Cave’s Sound Suit 2008. The suit’s voice is an embroidered tapestry of sequins and seashells, its skull determined both by its wearer and the elegant exoskeleton of metalflowered chandelier. The suit seems to want to walk out of the gallery, about to either exit or lead the fervent discussion continuing behind it.

Cave began making the suits in response to behavior surrounding the Rodney King beating and ensuing riots. Police were noted as describing King as an ‘unpredictable, threatening beast’. Cave’s suit seems a reflection of personified voicelessness, creating its own image from the negative space around its frame, the sound of movement rather than expression. It is a deity culled from the most human and universal of nightmares: the one in which one has lost the ability to scream.

Cave’s sound suit begins the discussion surrounding Working History with the notion of the body. Kara Walker and Io Palmer’s works continue this synesthetic skinning, appropriating bits and pieces of stereotype, hype, and historic gristle to enter into and further the conversation. Walker’s imagery employs some of the worst and most degrading of African American iconography in order to subvert it; she steals masks for the viewers benefit in order to feel what they are to wear in this day and time. Palmer works from a less pinpointed history while Hammons and O’ Grady comment upon the politics of history taught and re-examined with critical perspective. Here history becomes circumspect, its integrity as an academic entity disintegrated and made moot. The powers that be appear calcified, fossilized, strange healing tonics made of bourbon and chamomile, the advertisements for which would be laughed and marveled at to the effect of which they were believed. Taken out of context, played with, re-examined and rearranged, stripped and sutured, these artists reinfuse these objects and images with a sharper relevance. Placed next to each other in the gallery space, they foil and accentuate the physicality of identity. The recognition of others moving through space is rarely examined or felt, yet these pieces synesthetize this experience. Standing in the midst of them is like being in the center of a whirling vortex of voice, a catastrophic collective that bonds on the grounds of outrage and the effort to be made audible.

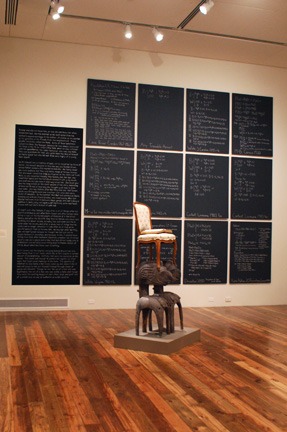

Continuing to move around the island in the center of the Cooley space, Kianga Ford’s chalkboard pieces loom cryptically, a lawful yet lyrical entity. While Ford’s attempt at fiction seems somewhat forced, the equations gleaned from years of the Census’ methods of determining what equals ‘black’ and ‘other’ are astonishing. The notion of comprehension is not as significant as is the idea of how these calculations resonate as the idea of statistic as fact. They are the wallpaper of an argument, based in analogy and what we feel to be part of reality, and who has the power to grant or create it. Someone, the little census people that live in the walls of official tell us that this is how we can measure blackness. As these census formulas move forward chronologically, the more apparent it becomes that the notions of ‘other’ and ‘minority’ as terms of description are no longer adequate. These groups of people have become more the norm and therefore the stigmas of the census’ categorizations fade into yellowed antiquity. This is the kind of knowledge that creates gaps in generations: the set of learning is no longer applicable to the living world, and a new way must be taught and learned.

This idea follows itself into the nook on the opposite side of the island as Snyder emphasizes the idea of change in mental awareness. David Hammons’ Holy Bible: Old Testament sits encased in its own glass box, an island on one side of a deep lake.

On the other side of this lake, Snyder has raided the Reed archives and set up images and articles illustrating the point in time when the Reed student body became racially integrated. Methods that had been taught and practiced suddenly needed to be revamped and reconsidered in order to address the new student body. As the new student body merely contained more humans, this concept is startling. Hammons’ Holy Bible: Old Testament sits just across the lake, and the echoing between the two is cacophonous. What trust do we place in governing bodies of knowledge? What ensues when they no longer carry the torch of authority? The way we see the world alters.

Walking out of the gallery space, two last very small, yet profoundly significant pieces call a quiet attention to themselves. They are the artist Dave McKenzie’s pieces, one on each side of the gallery entrance. These pieces seem to complete this exhibition as a poetic voice, welled from ethereal entrails. Where the other pieces in the show appropriate images and methodologies (both formal and ideological) to comment upon or around the impositions of the majority, MacKenzie’s pieces speak directly. They also address the notion of time as an almost non-entity. Time is after all, a human compartmentalization. Events repeat themselves, yesterday cannot be seen the same as today or tomorrow, and all is circumspect and yet somehow a given. History and the allegory of McKenzie’s Open Letters illustrate this.

Because as humans we are ultimately faulted, the cycles of behavior and thought repeat themselves infinitely. According to MacKenzie, each facet of these occurrences require amounts of compassion.

Snyder has compiled these artists into a philosophical discussion whose relevance and timing are incredibly apropos. As one of the most historically

significant elections our country has seen in decades draws near, and the war in Iraq rages on somewhat aimlessly, a reassessment of history and future require a re-examination. The pieces in Working History remind us that even history is in flux, to rest entirely on the laurels of our predecessors is dangerous, and our ability for thought is our greatest asset. What these artists give us is the representation and commentary of the gaps in the sputtering flux. Placed in one room together, the conversation they engender creates yet another kind of commentary as the voice of contemporary African America, never before understood or realized.