by Briana Miller

Originally published February, 2019

In 1975, the non-profit Friends of Timberline launched a project to recreate and restore the textiles of Timberline Lodge. At the time, only a handful of the original hand-hooked rugs, hand- appliquéd curtains, and hand-woven drapes created for the lodge as part of a massive Works Progress Administration (WPA) project remained. Over the years, since the lodge’s opening in 1938, the hand-woven upholstery that had covered the couches, chairs, and benches that were designed and crafted as part of the lodge’s original design program had also worn out and been replaced by commercially produced fabric.

With funding from the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act, the Friends of Timberline hired and trained eleven seamstresses and fabric artists. These workers and a team of volunteers ultimately recreated curtains following seven of the original twenty-eight guest-room themes and wove hundreds of yards of fabric to replace draperies in the lodge’s public spaces and upholstery for the lodge’s couches, chairs, and benches, all “in the spirit of the original,” as the lodge’s curator, Linny Adamson, describes it.

Margery Hoffman Smith (1888-1981) was the interior decorator who conceived and executed the original design program for the lodge. Returning during the restoration, she proposed replacing the plaid fabric that had replaced the worn original upholstery on the couches in the main lounge with turquoise Naugahyde. Hoffman Smith had always been a colorist.

Born in Portland, Hoffman Smith moved with her mother and brother to Boston when she was nine, following the death of her father. She attended schools in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and graduated from Bryn Mawr College, returning to Portland in 1911. Although she aspired to become a painter, by the early 1930s she had turned her attention to interior decorating. Accounts of how she was chosen for the Timberline project vary, but it seems likely that she was recommended by John Yeon, a young modernist architect, also from Portland. Yeon had developed designs for a ski lodge on Mount Hood, and while these weren’t selected for the project, he offered advice—ultimately not taken—to E. J. Griffith, the WPA administrator for Oregon, on where such a structure might best be sited.

Today, visitors to Timberline Lodge may see the warm, hand-woven upholstery and drapes in its public spaces as a nostalgic nod to the past. Similarly, the hand-appliquéd curtains in every guest room, with their graphic flowers, zigzags, and stripes, register as charmingly quaint. But when the lodge was completed, Hoffman Smith’s decorating program was startlingly fresh and very much of its time.

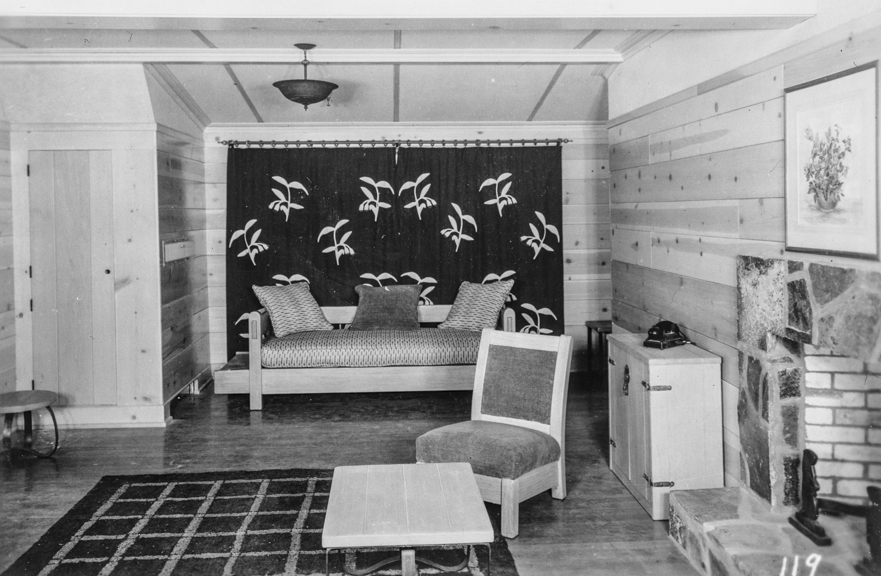

Under her direction, WPA workers hand colored and lettered several oversized books, now in the John Wilson Special Collections in Portland’s Central Library, cataloguing the textiles designed for each themed guest room. In these books, the bright colors of curtains, bedspreads, and upholstery nearly pop off the pages. Room 110, labeled “forest and stream” (fig. 1), features yellow sailcloth curtains with a geometric blue-and-green design. The room’s upholstery, woven of local wool, is rich blue with squares of dark green and aqua. The woven bedspread picks up the sunny yellow of the curtains and adds blue and green horizontal stripes. For the curtains of room 116, the “Indian pipe” room (fig. 2), large-scale cutouts of the wildflower are appliquéd on a green sailcloth ground. The upholstery and bedspreads are a mossier green, and the rug looks purple, although the catalogue describes it having gingham and turquoise stripes. “The color schemes were taken directly from the surrounding forests,” Hoffman Smith recounted, “with their rich and varied flora and fauna. Water color paintings of wild flowers were made to hang in the guest bedrooms, and in many instances gave the color key and patterns—the curtains having a stylized flower in appliqué—the bed spreads and upholstery picking up the dominant colors—the rugs a basic assimilation of all the colors.”

The rugs’ soft, modulated palette resulted from workers using worn-out blankets and uniforms collected from Civilian Conservation Corps camps and scraps from the state’s WPA sewing project. At the time, the Oregon sewing project produced 1,500 articles of clothing and accessories per day, from matching corduroy hats, dresses, and coats for school girls to pillow cases and sheets. Only eleven of the original 119 rugs created for the lodge survive. An inventory of these lists their materials as blue and pink cotton plaids and prints; light-blue cotton; black wool; and corduroys of creamy white, light brown, maroon, dark khaki, and light and dark blue. Rust, terracotta, and lavender also appear. It’s an evocative array of colors worn at the time, possibly by the very people hooking the rugs or by their families.

To Hoffman Smith, the location of Timberline Lodge was an “inspirational environment where pioneer background Indian tribal background afford endless design motifs.” Although she joined the project after the wildlife, pioneer, and Native American themes had already been established as the lodge’s design elements, her own design decisions carefully followed suit. Andirons and carved newel posts that fell under her purview depict stylized animals, such as a bear, beaver, fox, and eagle, and her choice to use hooked rugs and appliquéd curtains referenced Oregon’s pioneer past. However, she took an illiberal approach to Native American motifs, incorporating faux-Native symbols from a Campfire Girls handbook throughout the lodge—its “Wild Goose Moon” is now the lodge’s logo—and employing generically Native patterns in many of the themed guest rooms. “Indian pattern” describes room 216 (fig. 3), where curtains with angled clusters of blue and green triangles make a geometric pattern on a deep terracotta sailcloth ground, as well as room 305-307 (fig. 4), a ten-bed dormitory whose red sailcloth curtains have cream top and bottom bands crossed by black zigzags. For room 228, “Indian pottery” (fig. 5), green top and bottom bands on terracotta curtains each encase a single terracotta zigzag. While zigzags were a popular art-deco design motif starting in the 1920s—they referenced silhouettes of then new skyscrapers—here they were meant to conjure “Indian,” just not a specific tribe.

Significantly for Hoffman Smith’s rather vague cultural appropriations, some of the designs and patterns she used may have a regional connection. Her mother, Julia Hoffman, was known to be a great collector of Native American baskets whose collection included objects from tribes of the Pacific Northwest and the immediate area around Portland. Julia Hoffman’s collecting made her part of a “basket mania” that swept the U.S. in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when many bourgeois homes, including hers, featured “Indian corners.” It was also in keeping with her advocacy of the arts and crafts movement. After being actively involved in Boston’s Society of Arts and Crafts, Julia Hoffman founded the Arts and Crafts Society of Portland in 1907. She may have subscribed to the movement’s idealizing notions of “primitive” cultures, and Native American cultures in particular, as anti-modern models—with modernity the perceived source of many of society’s ills. “My early toys were Indian baskets and Indian bridles,” Hoffman Smith told an interviewer in 1974, explaining how her appreciation for well made objects was honed. The observation reflects how she and arts and crafts proponents such as her mother would have approached these Native materials: as beautiful and beautifully crafted.

Timberline Lodge was built in just fifteen months after the project broke ground in June 1936. While the lodge opened officially to the public in 1938, it was dedicated by Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the fall of 1937, putting additional pressure on the construction, design, and decorating teams to bring the project to substantial completion in time for the presidential visit. Eleanor Roosevelt had lobbied to fund projects under the Women’s Division of the WPA, which employed the Timberline weaving and sewing project workers. Room 107 (fig. 6), “Solomon’s seal,” was completed for her. Its design is less rambunctious than that of other rooms, with warm browns and creams and touches of henna tipping the beige pattern of the Solomon’s seal wildflower appliquéd on the curtains (fig. 7). One of the color scheme books was expressly created for Mrs. Roosevelt, who later donated it to the Multnomah County Library. The page for room 107 records in a careful hand that the room was occupied by Mrs. Roosevelt on September 28, 1937.

Mrs. Roosevelt’s interest in Timberline Lodge may have stemmed from the fact that it was a successful demonstration—at a much larger scale—of a project she had launched in 1927. With Franklin D. Roosevelt’s blessing, Mrs. Roosevelt and two friends opened Val-Kill industries in Hyde Park, New York, a non-profit factory where unemployed or underemployed rural workers were trained to produce high-quality reproductions of Colonial furniture. The factory was later expanded to include a forge and weaving.

While the Timberline Lodge project was government funded, most of the resources went to pay workers. “We had money for labor, unlimited labor, but not money for the materials,” Hoffman Smith recalled in a 1964 interview. The surfeit of labor available to her may have influenced her design decisions and certainly helped her accomplish the project within its aggressive schedule. “We didn’t have time to make a design, make a blueprint of it, and hand it to the weaver or the carpenter,” she said of the process. “I would stand over the weavers, having ordered the yarns, and I’d say throw so many, let’s throw it this way and let’s throw it that way through the shuttle.” Impractically

, Hoffman Smith conceived of 28 decorative themes for the guest rooms, from 8 luxe fireplace rooms to the third-floor dorms, which had 4, 6, and 10 beds. In the end, workers produced 119 rugs in 36 designs that used 45 color combinations and wove 136 yards of material for 10 drapes in the dining room, 322 yards for 52 bedspreads, and 564 yards to upholster chairs, benches, couches, and stools in the guest rooms and main lounges.

Today, the lodge’s housekeeping staff makes up rooms with fluffed white feather duvets and Pendleton blankets rather than thematically colored, hand-woven bedspreads. Most rooms have wall-to-wall carpet rather than hand-hooked rugs. For sheer scale, a decorating program like the ambitious one Hoffman Smith led would never be undertaken now. Maintaining twenty-eight different room themes would be impractical. Nor would furniture, fixtures, and textiles be handmade, given the high production and labor costs that effort would entail. The volume, speed, and complexity of the interior decoration program for Timberline Lodge was only possible because the driving purpose of the project was to put people to work. Hoffman Smith’s great achievement was that she was able to take full advantage of a nearly unlimited labor pool while remaining uncompromising on a sophisticated, albeit rustic, design scheme that was both comprehensive and cohesive.

Hoffman Smith left Portland in 1942, moving to San Francisco where her husband, Ferdinand Smith, became a partner in the investment firm now known as Merrill Lynch. After his death in 1959, she renewed her practice as an interior decorator. A photograph of a magnetic orange room in her San Francisco mansion that first ran in a 1967 issue of House Beautiful was republished in a 2017 article in the Boston Globe to show how bright colors, bold patterns, and global motifs enlivened home decoration in the 1960s. In the photo, at the edge of the frame, is a luxuriously long drape with gold bands, hand woven by Hoffman Smith. “I kept at it,” she stated in 1974 at the age of eighty-six, “because I felt that there was a great need of good color schemes, good color in carpets, good colors in curtains. I was pioneering for better taste.”

__________

1. Linny Adamson, interviewed by the author, September 9, 2018.

2. Annin Barrett and Linny Adamson, “Timberline Lodge Textiles: Creating a Sense of Place,” lecture, Portland Handweavers Guild, Multnomah Arts Center, Portland, Ore., January 10, 2019.

3. John Yeon, interviewed by Marian Kolisch, December 14, 1982 to January 10, 1983, tape recording and unpaginated transcript, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-john-yeon-12428.

4. Margery Hoffman Smith, “Interior Design of Timberline Lodge,” Design 45:9 (1944): 8.

5. Andy Harney, “WPA Handicrafts Rediscovered,” Historic Preservation 25 (July-September 1973): 11-15.

6. Sarah Baker Munro, Timberline Lodge: The History, Art, and Craft of an American Icon (Portland, Ore.: Timber Press, 2009), 221-22.

7. Hoffman Smith, “Interior Design of Timberline,” 6.

8. Richard S. Christen, “Julia Hoffman and the Arts and Crafts Society of Portland: An Aesthetic Response to Industrialization,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 109:4 (Winter 2008): 514.

9. Molly Lee, “Appropriating the Primitive: Turn-of-the-Century Collection and Display of Native Alaskan Art,” Arctic Anthropology 28:1 (1991): 12.

10. Margery Hoffman Smith, interviewed by Marian Kolisch, October 1974, San Francisco, tape recording, Oregon Historical Society Davies Family Research Library, Portland, Ore.

11. Margery Hoffman Smith, interviewed by Lewis Ferbraché, April 10, 1964, San Francisco, tape recording and unpaginated transcript, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-margery-hoffman-smith-12782. The following Hoffman Smith quote is also from this source.

12. Mary Elizabeth Starr, “The Textiles of Timberline Lodge,” Weaver 6:2 (April-May 1941): 4.

13. Sarah Munro, “Margery Hoffman Smith” The Oregon Encyclopedia, (Portland, Ore.: Portland State University and the Oregon Historical Society, 2019), https://oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/smith_margery_hoffman_1888_1981_/#.XB8xsPZFxes.

14. Marni Elyse Katz, “50 Years Ago, Home Design Got Its Groove On,” Boston Globe, July 23, 2017.

15. Hoffman Smith, interviewed by Kolisch.

Briana Miller is a freelance arts writer and marketing and communications professional. A contributing art critic for the Oregonian, she regularly reviews museum and gallery exhibitions in Portland. Briana returned to the Pacific Northwest in 2016 after nearly two decades in New York City, where she worked in marketing for architecture and architectural engineering firms. As a volunteer museum guide at the Brooklyn Museum, she led public and private tours of the permanent collection and of special exhibitions. She is a Fellow Emerita of the Institute of Classical Art and Architecture and remains involved in programing for the organization’s Northwest chapter. She is a graduate of Middlebury College (BA, Political Science/Spanish with a concentration in Art History).

This essay was edited by Sue Taylor, and is among a series of essays commissioned for the Visual Arts Ecology Project by The Ford Family Foundation with editors Stephanie Snyder, John and Anne Hauberg Curator and Director, The Douglas F. Cooley Memorial Art Gallery; and Sue Taylor, Professor Emerita of Art History, Portland State University. The commissioning institutions share a goal to strengthen the visual arts ecology in Oregon, and a key interest of increasing the volume of critical writing on art in our region.